Schimmel Scholars Annette Jun Diao and Renee Barbosa

Professor Emeritus of Biology Paul Schimmel PhD ’67 and his wife Cleo Schimmel are among the biggest champions and supporters of graduate students conducting life science research in the Department of Biology at MIT, as well as in departments such as the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, the Department of Biological Engineering, and the Department of Chemistry, and in cross-disciplinary degree programs including the Computational and Systems Biology Program, the Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience Program, and the Microbiology Graduate Program. In addition to the Cleo and Paul Schimmel (1967) Scholars Fund to support graduate women students in the Department of Biology, in 2021, the Schimmels established the MIT Schimmel Family Program for Life Sciences.

Their generous pledge of $50 million in matching funds called for other donors to join them in supporting the training of graduate students who will tackle some of the world’s most urgent challenges. Driven by their unwavering belief that graduate students are the driving force behind much life science research and witnessing a decline in federal funding for graduate education, the Schimmel family established their one-to-one match program. They reached the ambitious goal of $100 million in endowed support in just two years.

Back to the basics of gene regulation

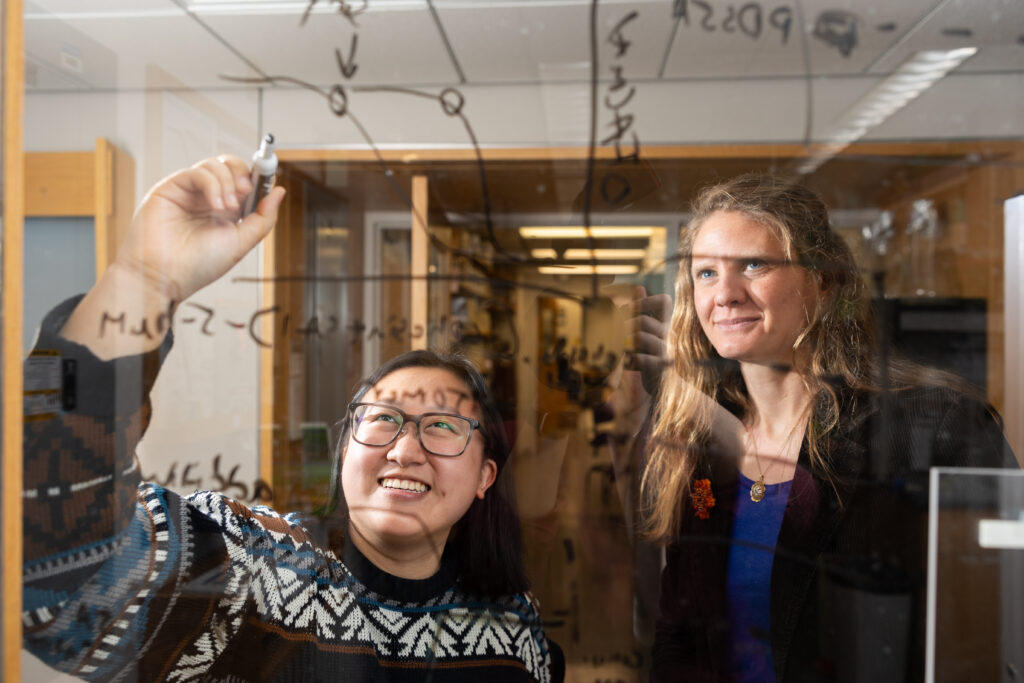

Graduate student and Schimmel Scholar Annette Jun Diao uses a minimal system to parse the mechanisms underlying gene expression

Annette Jun Diao’s mother loves to tell the story of Diao’s childhood aversion to the study of life — the gross and the squishy. Unlike some future biologists, Diao wasn’t the type to stomp through creeks or investigate the life of frogs. Instead, she was interested in astronomy and only ended up in a high school biology class because of a bureaucratic snafu. The physics course she’d been hoping to take was canceled due to low enrollment, and she was informed molecular biology was being offered instead.

She attended the University of Toronto and joined the molecular genetics department because of the numerous opportunities for hands-on research. She’s now a third-year graduate student in the Department of Biology at MIT.

“A huge advantage of the program was that I had a lot to choose from.”

“I’m fascinated by the mechanisms that underlie the regulation of gene expression,” Diao says. “All of our genetic information is in DNA, and that DNA is an actual molecule with chemical properties that allow it to be passed from one generation to the next.”

Every cell in our bodies contains a genome of approximately 20,000 genes, but the cells in our retinas are vastly different than the cells in our hearts — not all genes are in action simultaneously, and cell fates vary depending on how which genes are active.

“What is really awesome about the department — and what was attractive to me when I was applying to graduate school — is that I wasn’t sure exactly what methods I wanted to use to answer the questions I was interested in,” Diao says. “A huge advantage of the program was that I had a lot to choose from.”

Diao chose to pursue her thesis work with Seychelle Vos, the Robert A. Swanson (1969) Career Development Professor of Life Sciences and HHMI Freeman Hrabowski Scholar. Diao has been recognized with a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Fellowship, which is similar to a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship in the United States.

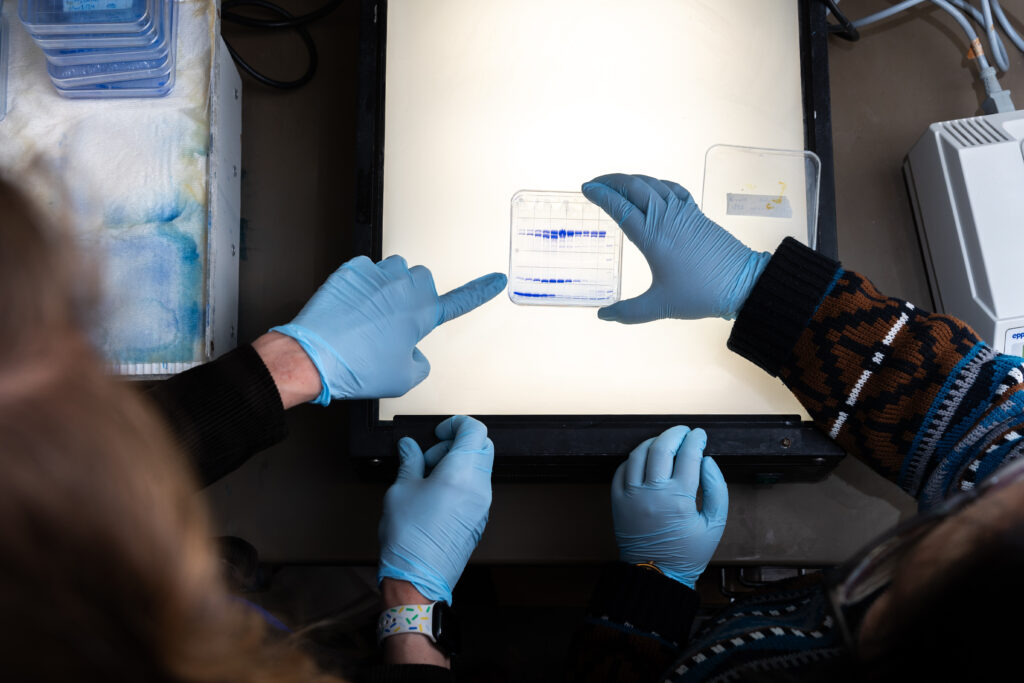

Vos’s lab is generally interested in understanding how transcription is regulated, the interplay of genome organization and gene expression, and the molecular machinery involved. Diao has been working with an enzyme called RNA polymerase II (RNAP II), the molecular machine that reads DNA and creates an RNA copy called mRNA. That mRNA goes on to be read by ribosomes to create proteins.

Many questions remain about RNAP II, including what signals instruct it to begin transcription and, once engaged, whether it will transcribe and how quickly it moves.

RNAP II doesn’t work alone. Diao is working to understand how a transcription factor called negative elongation factor associates with RNAP II and whether the DNA sequence affects that interaction.

Within the broader context of the genome, DNA is packaged extremely tightly; if it were allowed to unfold, its total length could stretch from Cambridge to Connecticut. What RNAP II has access to at any given time is therefore quite restricted, which Diao is also exploring.

She has been exploring this topic in what she refers to as a “reductionist approach.” By creating a minimal system — a strand of DNA and the precise addition of certain other isolated components — she can potentially parse out what ingredients and what sequence of events are essential “in order to really get to the nitty-gritty of how genes are regulated.”

Outside of her work in the lab, Diao is part of BioREFS, a peer support group for graduate students, and gwiBio. Both organizations bring members of the department together for scientific talks and socializing activities outside of the lab, and gwiBio also participates in community outreach.

Diao is also a Schimmel Scholar, supported by Professor Emeritus of Biology Paul Schimmel PhD ’67 and his wife Cleo Schimmel.

“It was really great to learn that I was being supported by a scientist who has done a lot of awesome work that’s relevant to my world,” Diao says.

“It is awesome that they are so committed to supporting the graduate program at MIT, especially when federal resources have become more limited,” Vos says. “With their support, our lab can train basic scientists who can then use their knowledge to transform our study of disease. I hope others follow Paul and Cleo’s example.”

Lillian Eden | Biology

RNA processing and gene expression governing

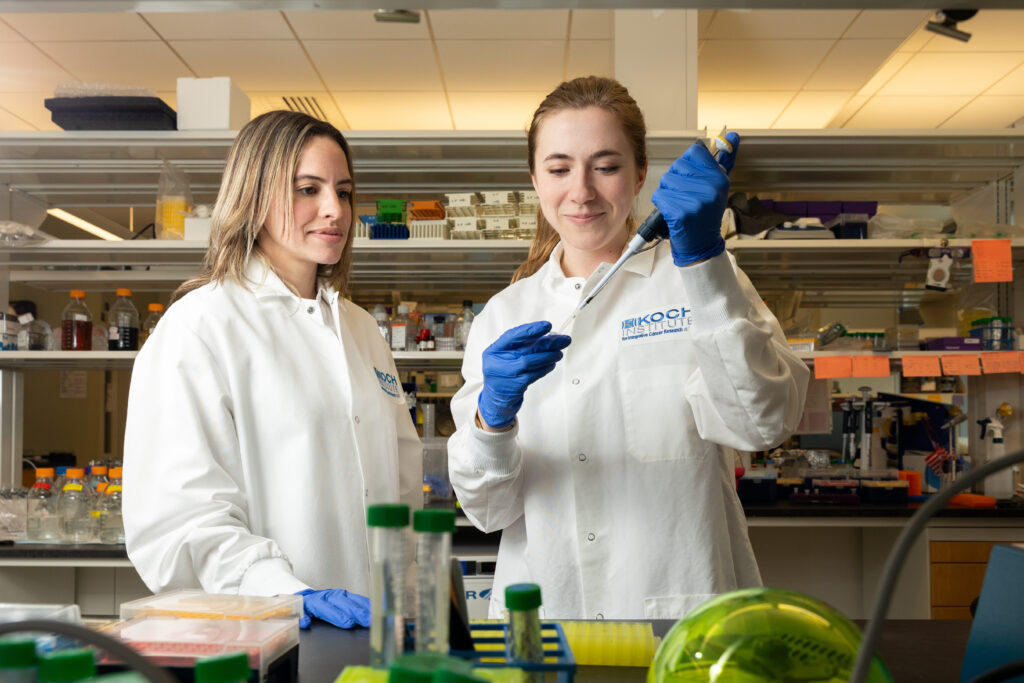

Graduate student and Schimmel scholar Renee Barbosa studies chromatin’s role in gene expression

The discovery that mutations in genes can drive cancer revolutionized cancer research. In the decades following the identification of the first “oncogene” in a chicken retrovirus in 1970 and the first human oncogene in 1982 by Robert Weinberg at MIT’s Center for Cancer Research, scientists uncovered hundreds more oncogenes, transformed our understanding of how cancer begins and progresses, and developed sophisticated gene-targeted cancer therapies.

A majority of oncogenes were identified in factors controlling cell signaling, proliferation, and differentiation. However, a growing understanding of epigenetics has shown that many cancers, such as some leukemias and sarcomas, are not driven by mutations to these factors themselves, but by disruptions to the molecular pathways that regulate their expression. About 10 percent of all leukemias are driven by abnormal versions of the protein MLL1, one cog in the epigenetic machinery controlling these factors.

Renee Barbosa, a graduate student in the laboratory of Howard S. (1953) and Linda B. Stern Career Development Professor Yadira Soto-Feliciano in the Department of Biology, is joining this next wave of research, using leukemia as a model. A member of MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Soto-Feliciano and her lab study chromatin, the densely coiled structures of DNA and scaffolding proteins that make up our genomes and help ensure genes are expressed at the right times and in the right amounts.

Barbosa focuses on the role of RNA processing and the precisely choreographed alterations to chromatin that govern gene expression. RNA molecules serve as messengers between DNA and its final product, protein, and are subject to extensive processing and regulation. However, not much is known about the interplay between RNA processing and epigenetic machinery, particularly in cancer.

“I hope that my work will uncover additional layers of complexity in the dynamic landscape of gene regulation,” says Barbosa. “It might also identify new mechanisms that can be targeted to help treat leukemia and other cancers.”

Before Barbosa arrived at the Soto-Feliciano Lab, she was already steeped in the molecular intricacies of cancer.

While at the University of Pennsylvania, she earned a BA in biochemistry and biophysics concurrently with a master’s degree in chemistry. Early on, she joined the lab of Ronen Marmorstein, which used molecular approaches to characterize MEK and ERK, two cancer-relevant members of a class of signaling proteins. Upon starting graduate school, she was excited to branch out into other disciplines.

Barbosa has always taken every opportunity she can to learn. Beginning in grade school, science and math were her favorite subjects, but she also explored music, dance, and foreign languages. At the University of Pennsylvania, she even squeezed in a minor in neuroscience.

With its interdisciplinary approach, the Soto-Feliciano Lab provides Barbosa ample opportunities to learn. Because epigenetic factors can elude traditional approaches, the Soto-Feliciano Lab uses a multidisciplinary strategy, ranging from molecular, to large-scale omics analyses, to disease modeling.

“When I was a grad student, we saw the arrival of powerful new massive sequencing and gene editing technologies — and were enabled to ask big new questions,” says Soto-Feliciano. “I am excited that Renee will have even more resources and opportunities, as we enter the next stage of cancer genetics and epigenetics.”

With the support of a Schimmel Fellowship, Barbosa will be ready to take advantage of new developments in her field.

“Support for research early on in graduate school is an incredible opportunity,” says Barbosa. “It means time to delve deep into the literature of the field and identify challenging open questions that I can pursue in my project. Though exploring these unknown areas requires taking bigger risks, I hope that we will get invaluable insight from an understanding of these nuanced and complex mechanisms.”

Bendta Schroeder | Koch Institute